Generally, as economists, we are interested in how production is organised and how what is produced is distributed among consumers, all of which occur in markets (those specific institutions we are all familiar with). In the middle of all this comes a concept that we sometimes do not have very much in mind, the theory of general equilibrium or the Walrasian general equilibrium theory after the name of its developer Léon Walras.

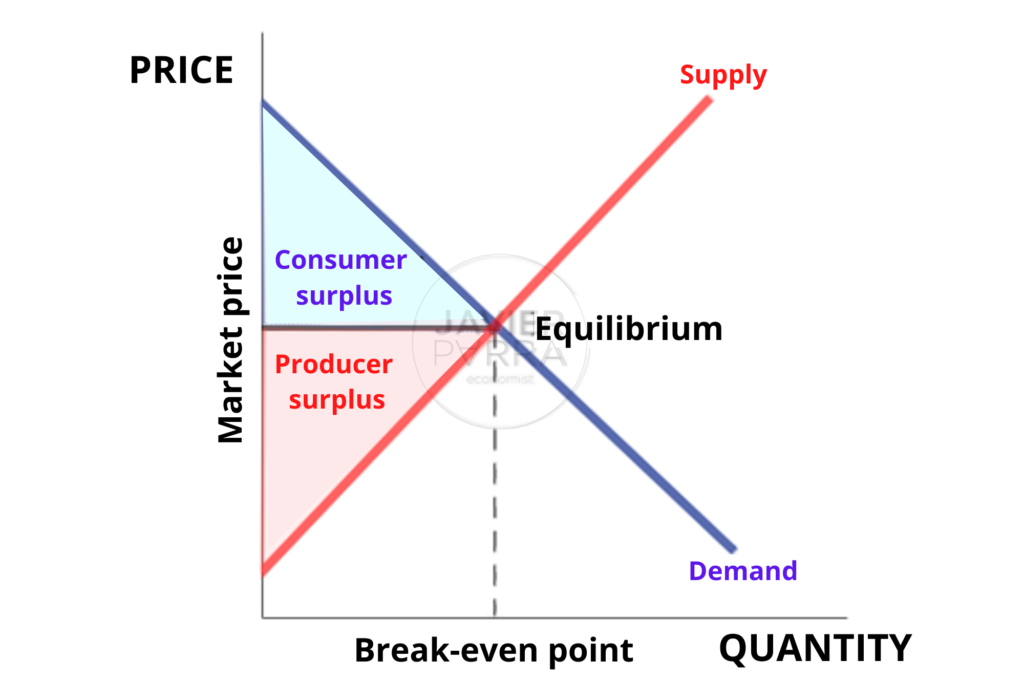

The theory of general equilibrium is a macroeconomic theory that explains how in markets, there is a dynamic interaction between supply and demand, which eventually culminates in a price equilibrium. In economics, economic equilibrium is when the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded are equal. Therefore, this theory aims to identify precisely the set of circumstances that must be in place for the equilibrium price to be very likely to reach stability.

This is a market system where the consumption of goods and services are closely related because varying the price of one good affects the price of other goods. In that sense, the basic questions in general equilibrium analysis concern the conditions under which equilibrium will be efficient, what equilibria can be reached, the existence of an equilibrium guaranteed, and when the equilibrium will be unique and stable.

Demand Vs Supply

Resource allocation is rooted in how societies seek to balance limited resources such as land and working capital against the needs of their members through various mechanisms, the best-known allocation mechanisms being the household, business and government.

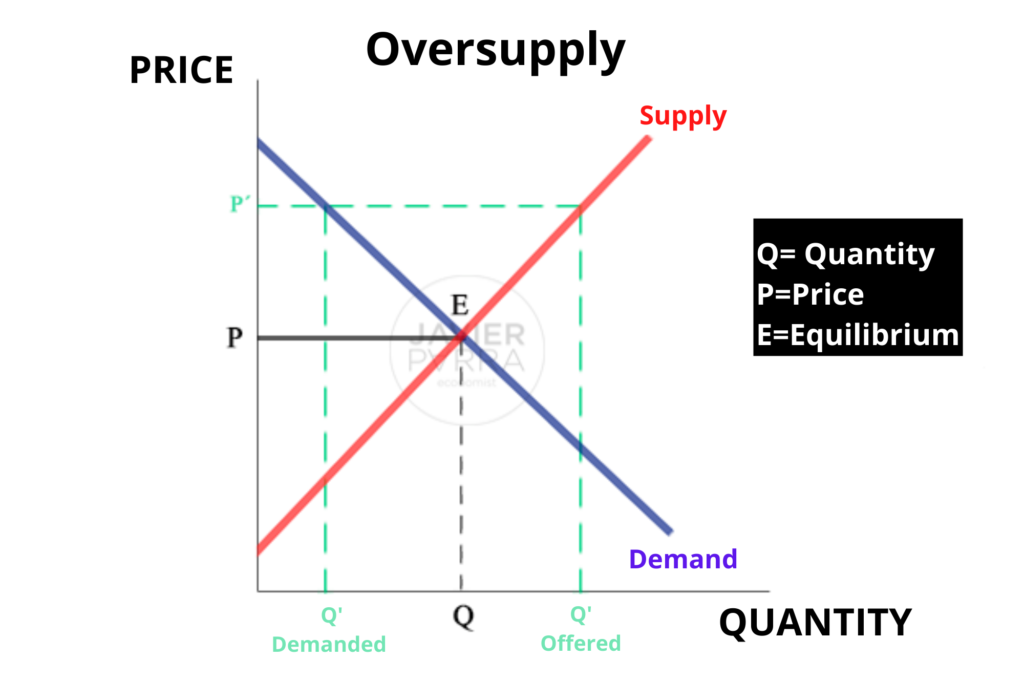

For example, when the real price is above the equilibrium price, many producers will be interested in offering the product, so the quantity offered will increase. Still, because prices are so high, there will be less demand leading to excess supply.

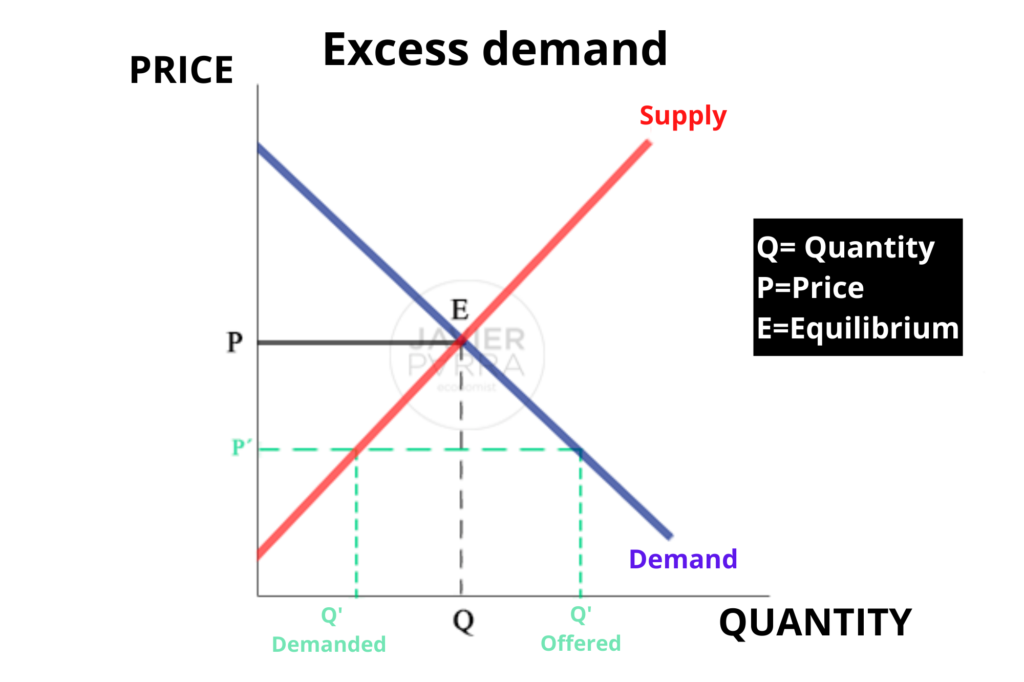

In the opposite case, when the real price is below the equilibrium price, there will be fewer producers offering the product and more demanders willing to buy it, which will lead to excess demand.

Léon Walras and his theory of general equilibrium

The theory of general equilibrium is related to Léon Walras as who wrote “Elements of pure economics” in 1874. Still, the term had been used (albeit loosely) by other economists before that.

Walras was the first to give depth to the idea, and his explanation began by describing an elementary economy in which there were only two goods that could be exchanged, which he called X and Y. In this economy, it was assumed that all goods in the economy could be exchanged. In this economy, it was assumed that everyone was a buyer of one of these goods and a seller of the other. What Walras proposed in this system was that:

- Supply and demand would be interdependent since the consumption of goods X and Y would depend on the wages derived from the sale of these goods.

- The price of goods X and Y would be decided by “tâtonnement”, i.e. by a bidding process.

So Walras argued that we could take this in terms of an individual seller who indicates the price of a good in the market, and it is consumers who respond by buying it or refusing to pay it. This would be through the process of trial and error as the seller must adjust the price to match demand, thus arriving at the equilibrium price. Thus, there would be no exchange of goods until the equilibrium price was reached, an assumption that led him to be criticised by other economists.

Walras took this principle of general equilibrium theory to an environment with multiple markets by introducing a third well into the process, which he called Z. Thanks to this third element, three price relationships could be determined (one of which would be redundant because it only provides information that could be deduced from the others). This redundant good was identified as the standard through which other price relationships could be expressed; it would guide exchange rates.

We can safely say that Walras’ theory had a disruptive effect on the way markets were viewed, previously a more philosophical and literary theory and came to be regarded as a deterministic science. His insistence that economics can be reduced to a disciplined mathematical analysis remains. Another of Walras’ achievements is that he blurred the line between macroeconomics and microeconomics as the relationship between household and business economics cannot be seen as separate.